Interweaving #29 - Catherine Tedford on Political Stickers from WWI to the Age of COVID

FC St. Pauli sticker, “Refugees Welcome”

In this episode of Interweaving, host John Collins speaks with Catherine Tedford, curator of the Street Art Graphics digital archive. They discuss her work collecting and analyzing political stickers from around the world and look at examples of stickers expressing a wide range of views on social and political issues ranging from war and workers’ rights to refugees and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Featured in this episode

All images courtesy of Catherine Tedford. Items in her digital archive are made available for education and research. Viewpoints expressed in certain items do not necessarily represent viewpoints of the archive’s curator, contributors, or any others related to the project. Items may be protected by copyright. You are free to use the items in any way that is permitted by copyright and rights legislation that applies to your use. For more information, see http://rightsstatements.org/page/InC-EDU/1.0/.

Click and hover to view image titles.

Street Art Graphics Digital Archive

https://www.jstor.org/site/stlawu/street-art-graphics

“Sticky Art: The Street Art Graphics Collection”

https://www.artstor.org/2017/01/04/sticky-art-the-street-art-graphics-collection/

Richard F. Brush Gallery at St. Lawrence University

https://www.stlawu.edu/offices/art-gallery

The Social Movement Archive

https://litwinbooks.com/books/6722/

Hatch Kingdom Sticker Museum by Oliver Baudach

https://en.hatchkingdom.com/pages/galerie

https://www.stickerkitty.org/close-up-hatch-kingdom-sticker-museum/

“Paper Bullets: 100 Years of Stickers from Around the World”

https://www.stickerkitty.org/paper-bullets-the-expanded-version-at-neurotitan-gallery-in-berlin-germany/

https://www.flickr.com/photos/stickerkitty/collections/72157716998071328/

“U.S. I.W.W. ‘Stickerettes’ or ‘Silent Agitators’”

http://peopleshistoryarchive.org/exhibit/us-iww-stickerettes-or-silent-agitators

Stickerkitty blog

https://www.stickerkitty.org/

“Covid-19 Conspiracy and Anti-Vaxx Stickers in Potsdam, NY”

https://www.stickerkitty.org/covid-19-conspiracy-and-anti-vaxx-stickers-in-potsdam-ny/

Transcript

John Collins: Welcome to Interweaving. I’m John Collins. “Ubiquitous in urban centers around the world, publicly placed stickers grace every imaginable surface of the built environment, addressing both the personal and the political, the mysterious and the mundane.” What I’ve just read is an introductory statement from something called the Street Art Graphics digital archive, housed at St. Lawrence University. It’s a fascinating collection of political and artistic stickers from over 40 countries. And we’re very fortunate to have with us today the person behind this unique project. Cathy Tedford is the director of the Richard F. Brush Art Gallery in Canton, New York. She’s also an internationally recognized collector and analyst of political stickers. Cathy, welcome to Interweaving.

Cathy Tedford: Thank you, John.

So I wanted to talk with you about your work with political stickers, because I think it’s really tempting to assume that the political world has been completely overrun by moving images and also by the power of social media. But the power of physical stickers occupying public space has never really gone away, has it?

John, I’m going to respond to that question with part of an essay that I’m working on for a new publication coming out called “Unframing the Visual: Visual Pedagogy in Libraries and Academic Spaces.” So this is the intro to that essay.

“Publicly placed stickers with printed images and/or text have been used for decades as a means of a creative expression and as an effective way to engage passersby. Often spotted at eye level or just beyond reach, stickers are hidden in plain sight, gracing every imaginable surface of the built environment from street signs and utility poles to fence posts and garbage bins. Stickers also adorn laptops, water bottles, and musical instruments, appealing to diverse audiences through eye-catching visual designs and powerful messages that carry a punch. Though ephemeral by nature, stickers capture the creative cultural, and socio-political pulse of time and place. In the United States, as early as the 1910s, the Industrial Workers of the World created what they called ‘stickerettes,’ or ‘silent agitators’ to oppose poor working conditions, intimidate bosses, and condemn capitalism. During World War II, Allied and Axis forces dropped propaganda leaflets, stickers, and gummed labels known as ‘paper bullets’ and ‘confetti soldiers’ over enemy countries as a form of psychological warfare, and in the US during the 1960s and seventies, nightraiders protested the war in Vietnam and American imperialism, while others called for racial and gender equity. During the 1980s and nineties, stickers rose in popularity within the do it yourself (DIY), punk and skateboard subcultures, and are now ubiquitous in urban centers worldwide. Today, stickers may be used to tag or claim a space and make it temporarily one’s own, sell products and services, announce events and activities, publicize blogs and social media sites, and/or offer social and political commentary and critique.”

Thanks for sharing that with us. This such an interesting topic, not least because so much of this material is all around us, and yet we don’t often really notice that it’s there. And so becoming aware of how much of it is out there and really training yourself to look at it, I think is incredibly important. It’s something that I’ve learned from your work. And so I wanted to begin by asking you what got you interested in stickers. And how did you end up building such a large and diverse collection of stickers from around the world?

Sure. I’m going to read one more quote, and then I promise we’re going to go into more conversational mode here. This is from a book that came out in 2021 called The Social Movement Archive, which featured a chapter on my project, edited by Jen Hoyer and Nora Almeida.

“My interest in political art goes back to my childhood. My father was a congregational minister and a community college professor. He was active in several social justice movements, civil rights in the 1960s and seventies, the anti-Vietnam war movement, and women’s rights struggles. I grew up with posters around the house by Sister Corita Kent and the iconic poster ‘War is not healthy for children and other living things.’ My dad instilled in me the idea that here in the United States, democracy and good citizenship meant ensuring equal rights for everyone, every single person, as well as equal access to healthcare and education. I majored in printmaking in college and graduate school. Printmaking is often considered the most democratic form of creative expression, at least before stickers became so popular. And I saw printmaking as a way to advocate for the kinds of values my dad instilled in me.”

After printmaking, making and collecting political stickers was a logical next step as I look back on it now. But, more recently, I first discovered the power of publicly placed stickers while traveling to Berlin in 2003. And I was aware of stickers, of course, commercial stickers and comic stickers and things like that. But walking around Berlin, I stopped in my tracks at the rash of stickers everywhere in that city. And it really changed my relationship to the city itself, actually, because I stopped looking at city lines and building skyscrapers and things like that, and I was crawling up street signs and looking on the backs of dumpsters and, you know, just fascinated with the wealth of stickers in that city. And Berlin is known for its sticker scene, in part because it’s historically been so poor since the fall of the Berlin Wall. It’s become much more commercial, but it’s still a city that’s really rich with stickers.

I gave a paper presentation in 2008 at College Art Association. It was my first conference paper on stickers. And a couple of months later, I got an envelope from a man named Fred Lonidier. And he sent me stickers from the SDS, which are the first historical political stickers that I had ever seen that I remembered. My father could very well have had some, but...

Students for a Democratic Society

Right. And so that immediately changed the focus of my research toward political stickers. I had been up until then looking at various graffiti stickers and art stickers and some political stickers in New York City and Berlin and elsewhere in my travels. But getting these original stickers from the SDS just gave me my focus.

So one of them here says “Mississippi, Vietnam, freedom is the same all over.” Another sticker says “Genocide for fun and profit, support US foreign policy.” There’s a Bertolt Brecht quote. They’re just so brilliant. These are gummed labels that are just so powerful. There’s something so immediate about them.

I met someone named Oliver Baudach in 2009 in Berlin, who runs what was then called the Hatch Kingdom Sticker Museum. And he and I formed a very close partnership, and I owe Ollie such a huge amount of thanks. He’s been my greatest supporter. He’s collected political stickers for me, mostly from Germany, but from Spain and elsewhere. And he and I have collaborated on, going on now four traveling exhibitions of stickers. The most exciting for me was a show that we did in 2019 called Paper Bullets: 100 Years of Political Stickers from Around the World. Premiered in Berlin and we’re hoping we’ll go to Barcelona next year.

That’s fantastic!

Yeah, I’m really excited. So I also, I guess I wanted to mention where I get stickers. Aside from Ollie, I’ve got some contacts here in the States. I picked up some small collections of political stickers from eBay in Spain and eBay in Germany. But moreso I go to anarchist book fairs and alternative bookstores. Berlin has a very active May Day celebration where the political parties come out in tents and share ephemera. Most, I would say, the political parties in Germany use stickers to communicate their messaging, unlike anything here in the States where you might get a simple, whoever, politician’s name, they’re rarely issue oriented political stickers here in the States like they are in Germany and Spain and elsewhere. So that’s where I have acquired most of my stickers.

I appreciate the deeper history behind it as well, because I can imagine being surrounded by some of those classic 1960s era posters and the powerful graphics. I remember some of those from my own childhood as well from my parents and my grandparents. And so we can see the through line from that to the focus on political stickers today.

So I wanted to learn a little bit more about your process once you kind of come into possession of particular stickers, and sometimes you’re probably trying to figure out, what does this mean? Where does it come from? So when you come across an interesting sticker, how do you approach the process of making sense of it?

This is a process that I use myself, and I’ve also used in classes here at St. Lawrence when students are writing about stickers. And basically I start with what I call an inventory, a visual inventory and a textual inventory, so that I really make a very concrete list of all the images in a sticker, every detail. I list out all the texts in a way that makes logical sense.

And so I pulled a sticker that I thought we could take a look at together. It’s from the football club St. Pauli from Hamburg, Germany. And it depicts three young boys sitting in front of a bookshelf. It looks like a family photo. There’s one boy that’s smiling and two boys that are crying in the front. And so I’m going to unpack this a little further. The boy in the back has a Football Club St. Pauli logo emblem on his shirt, and he’s wearing brown and white, which are the team’s colors. And the two boys in front have rival team logos on their shirts and the same, you know, team colors. But what I find really interesting about this image is that the boy smiling has dark hair, and the two boys in front have blonde hair. And in Germany, that’s very different than what we see here in the States. So it’s a comment on ethnicity, I think, and German nationalism. What would you say, John?

Yeah, that definitely jumps out at me as well. I should mention for our listeners that all of the images that we’re discussing today will be available on our website as part of the show notes for this episode. So you can look at those on the website as you’re listening to our discussion of them. And you’re right, this particular sticker reads immediately as an awkward family photo, right? It reads as one of those classic photos that you maybe would get taken at Sears or something like that, of young kids. But yeah, the kid in the back, you know, has dark hair and looks different, right, from the two blonde kids in the front. And that’s one of the, that’s one of the visible elements of it immediately along with the football club logos that they’re all wearing. If someone were just looking at it and it doesn’t know much about Germany or German football, they might miss a lot of that context and not even really understand what they’re looking at, right?

Yeah, exactly. So I know when I first started looking at German stickers and translating and, you know, a lot of use of symbols that I was unfamiliar with. It just takes some digging around, you know it’s stuff that’s accessible, certainly, online, but it just takes some digging and kind of keeping a mental track of various images and symbols.

So each sticker is an invitation to investigate and to learn, right? Yeah. So you’ve brought a number of other stickers in today as well. Let’s take a look at another one.

Well, the other one I wanted to talk about was what I had talked about at the beginning, the IWW stickerette or silent agitator. And I love that phrase, “silent agitator.” You know, when you’re walking down the street and you see something stuck up on a sign, it’s not obviously vocal. But it does carry a punch. This particular sticker I’ll read aloud. It’s using the four different suits in a card deck. And so the text and the suits combined read as follows: “The capitalist’s heart is in his pocketbook, and he uses the club over you so that he can wear diamonds. By organizing right, we can give him a spade with which to earn an honest living.” This sticker was created in the mid 1910s, and they were printed by the millions, apparently. Stickerettes would be found on job sites, on train cars, peppered everywhere. And that history is fascinating to me, that the stickerettes were produced in the numbers that they were. They’re very hard to find today. But they live on for sure.

And this particular one, just to put it in context, so this comes out of a US context, right?

US Industrial Workers of the World, yep.

Right. And so the fact that these were printed and distributed by the millions is quite remarkable, right? Just in terms of understanding the history of that period. What do we know about the people who made them and how authorities and other groups responded to them for producing a sticker like this?

Well, in the 1910s, Ralph Chaplin is one of the artists I know of. He was one of the first artists to create stickerette designs. He was an editor of Solidarity and some other journals, but he and several others were actually arrested by the US federal government in 1917 for violations against the Sedition Act, I think it’s called. The stickerettes were used as evidence in the court case that the IWW was promoting antiwar sentiments. And so the stickerettes have a place in history, actually.

A place in history as representing a particular kind of antiwar organizing that was connected with workers’ movements. Strikes me as particularly important in terms of understanding why it is that organized labor at that time would have been skeptical of claims that we need to go to war.

Right. Exactly.

So what other kinds of stickers tend to grab your attention right now? And do you have any others that you want to show us today?

Sure. I’ll pull a few more from the St. Pauli Club here and then also talk about some stickers from Hatch Kingdom. I’m very fond of stickers that do what’s called culture jamming, where symbols and logos and images are manipulated to create new interpretations. Well, and also the use of pop culture in stickers. The St. Pauli Club uses many, many different US pop culture icons including Che Guevara. This is Homer Simpson dressed as Che Guevara. There’s a sticker here that riffs on the Jaws poster, the Gorillaz figure, the band, Popeye, you know, the list goes on. So I’m interested in those.

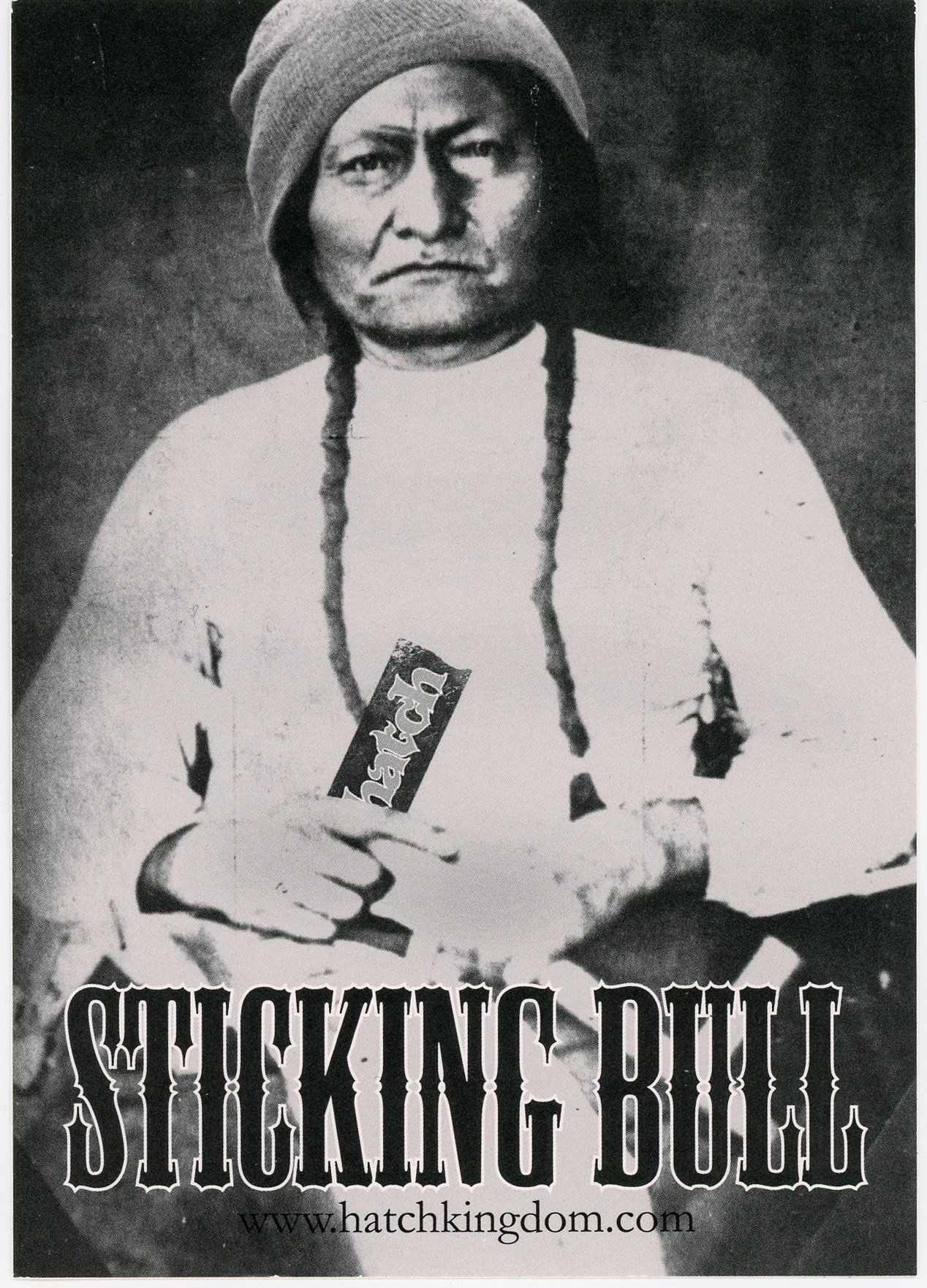

But also I wanted to show a sticker or two from Hatch Kingdom. Ollie does a lot with culture jamming. And so we’ve got a sticker here called Sticking Bull where we’ve got a figure, Sitting Bull, holding a Hatch sticker and wearing Ollie’s classic wool cap here. There’s another sticker, again, Napoleon Stickaparte, with Ollie’s signature wool cap. So those are the stickers I’m drawn to. I’m drawn to all the stickers. I mean, it’s like I can’t make choices!

But the culture jamming stuff and the use of recognizable pop culture...

In different contexts.

...images, is important because it tells us something about which aspects of American culture have gotten traction in other places. And then it’s those elements, correct me if I’m wrong, but I assume it’s those elements that are expected to draw the viewer’s attention so that they will then also notice what else is going on in the sticker and catch the deeper meaning of it.

Right. And so the figures here often represent the ne’er do wells in pop culture. You know, the stickers are appealing to all of us ne’er do wells, you know, or the imps, the troublemakers. One thing I did not say at the beginning, and I need to preface, the reason I chose the football club St. Pauli is because they are the most outspoken, anti-racist, anti-fascist, anti-sexist team around the world. And so they are known for their political stance on a variety of issues, immigration, refugees in Germany. And so they’re unlike any other team that I know of. There’s one sticker here that says “Refugees Welcome,” you know, with the St. Pauli logo on it. They have various political campaigns that put money to refugee camps, and they put their money where their mouth is. And so they’re using this as a way to raise awareness.

And in urban environments, big cities like Berlin or New York and others, we’re constantly being assaulted by, surrounded by, the logos of big corporate brands. That’s part of the privatization of public space. And so it’s really, really fascinating to me how sticker artists are able to take those logos, not to make them disappear, but to make them visible in a different way so that we become aware of how ubiquitous those logos are and how much they control our surroundings.

Exactly. And, you know, speak truth to power, basically. Talk back to power.

Also with us today is Skylar Bergeron who was working as a Weave News intern this summer in our Editorial Coordinator role. Skylar, I know you spent several months living in Madrid, Spain, recently, and paying attention to what was happening politically and culturally in the city while you were there. I’m wondering if any of this that we’ve been discussing so far resonates with you and the experience that you had in Madrid.

Skylar Bergeron: I think there’s a lot of connections to be made here. To me, it sort of seems like a way to show, I guess the different layers of the city and its culture, something that I noticed, for example in Chueca, which is Madrid’s historic gay neighborhood that I spent a lot of time researching and doing observations in. There’s certain parts of that neighborhood that are very touristy and draw a lot of attention. And those areas have on the walls painted, you know, saying it’s prohibited to put up flyers here or posters. But then in that same neighborhood within, I don’t know, a mile radius, there are still lots of street art, lots of stickers, all kinds of material like that.

And so to me, I think that’s where a lot of the power of street art comes from is that it never really goes away. And something like that, even when it may be legally prohibited, it still pops up. And I think that in that way, it’s a sort of a visual representation of a city or geographic region’s culture and which parts are suppressed and which are more mainstream. I don’t think it’ll ever go away, and I think that’s why it’s powerful.

Yeah we certainly see from all of these examples that authorities of different kinds always have an interest in trying to police the creation and the circulation of this kind of material and this form of expression. And again, whether we see that around World War I, or we see it today in Spain, these are struggles over public space and who has a right to express themselves, and how, in public space. And that, to me, that’s one of the themes that comes out so strongly in the work that you’ve done, Cathy, is that we can’t help but see those struggles once we start paying attention to the stickers themselves.

Exactly. I mean, in certain neighborhoods in Berlin that are becoming gentrified at such rapid pace, the stickers speak very directly to commercialization and trying to reclaim old neighborhoods, things like that. It’s very apparent.

Now, some people might assume that political stickers mostly represent leftist positions, radical positions, progressive positions. And that may be true. But that’s not always the case, right?

There are stickers representing every range of opinion you can imagine. I’ve got KKK stickers, a few, not many, in the collection. I have found white power stickers right here in Potsdam, New York, 10 miles down the road, on three different occasions now in the last couple of years. And most recently two different sets of what I call COVID misinformation stickers, the first of which was in New York City last November, 2021. I was down for a weekend and had heard that the Proud Boys were going to be marching in Manhattan. And so I thought, hmm, I bet there’s gonna be some stickers over there. And so I walked over, my husband and I walked over to Grand Central Station where we knew they had been. And Lexington Avenue was just covered with stickers. There were probably 10 or 11 stickers on every block.

I ended up walking down 24 blocks along Lexington Avenue and found 72 different designs. And these are low, very low tech, they say “brought to you by the White Rose,” which was a movement during World War II, an anti-Nazi movement. And so this COVID misinformation campaign is now adopting the anarchist name in its efforts to spread COVID misinformation.

Could you maybe describe one of those stickers and exactly what we see on it to give us a sense of what a Right sticker in 2021 looks like?

Sure. Well, this is another interesting one. There’s one here called “Keep your country clean.” And it shows a very rough, simple figure of someone throwing a communist symbol into the garbage can. And this is another rip on left-wing stickers, where a person is throwing a Nazi symbol into a garbage can.

There are several stickers that claim that “F is for fraud,” and there’s a picture of Dr. Fauci, “Stamp out Faucism.” Again, here Fauci is given a Hitler mustache and hair line that looks like Hitler. So just a really weird play on appropriating left wing imagery for right wing conspiracy messages.

It strikes me as an effort to create confusion in the world of images and iconography so that political positions that might’ve seemed clear to people will start to feel blurred and uncertain.

And I’m glad you brought up the example of the stickers that you found here in Northern New York as well, because it’s important to recognize that even in a rural area, there are political groups, whether they’re on the left or on the right or otherwise, who are using the form of stickers to express their viewpoints. And I wanted to mention to our readers that Cathy often documents these kinds of examples on a blog called Sticker Kitty. And we’ll be linking to that as well, so that you can explore more of the kinds of examples that Cathy works with and the analysis that she provides of those on her blog.

Despite the Sticker Kitty name, “Kitty” is a play on Cathy. The blog is very serious, and I take the research very seriously.

So if we step back from these kinds of examples, let’s talk a little bit about the broader significance of this particular form of cultural and political expression. So what can we learn from studying political stickers?

We can certainly learn any amount of research on any topic. Honestly, there’s not a topic I can think of that has not been addressed in a sticker. If you take a few minutes and do some research, first pay attention to the world around you, and when you’re mostly in an urban environment, take a look at the signs and the light poles and windows and storefronts. The stickers are there and everyone I’ve talked with, everyone who becomes familiar with my work, says they can’t walk down a city street the same anymore. It really does change your perspective on your relationship to the world around you.

I’m going to read one more short quote. “I would argue that publicly placed stickers invite us to reconsider our relationship with the world around us, which is no small feat. In his book Gestures of Concern, Chris Ingraham writes that stickers can be used to ‘create surprising public experiences, to stoke curiosity, revitalize perception, and reorient people with a new found attentiveness to what’s around them.’ And that more generally, stickers are part of ‘efforts people make to join in public affairs in ways that feel participatory and beneficial though their measurable impact remains imperceptible.’ He argues that the ‘force of gestures like stickers affirms a sense of something more intangible, call it kinship, empathy, solidarity, kindness’.”

And I really love that quote so much. It’s, I think, very important these days in a world right now of such divisiveness, kinship, empathy, solidarity, and kindness go a very long way.

Indeed they do. You’ve been working on this stuff for a long time, and obviously you’re much more attentive to the details of what’s out there than most of us are. So what are you looking for, as you look forward in terms of where stickers are going, what’s really interesting you right now, and what you anticipate, you know, in the coming years, that will be the focus of your work?

I think that stickers, as Skylar said, will endure. I think they’re so simple, they’re so easy. Anyone can make a sticker. People have something to say. That’s another thing I say a lot. Everyone has something to say. And they’ll say it quickly and easily on a sticker slapped up on the side of a wall.

One thing that disappoints me a little bit about stickers is how difficult it becomes to find them as public spaces become privatized. After having gone to Manhattan now, really since about the early 2000s, when certain neighborhoods would be covered with stickers, stickers now in Manhattan are very difficult to find anywhere. They have paint with grit in it that they put on public fixtures that make it impossible to put a sticker on. And that depresses me quite a bit, actually. So I tend to seek out the poorer neighborhoods where people actually can say something about the world around them. So those are the places where I will be.

That makes a lot of sense. We recently published a piece over at Weave News as part of a series called Weaving the Streets that Cathy and I are both involved in editing, and it’s a piece about Madrid again, written by a student who spent time in Madrid and was looking at graffiti in particular, and commented that in Madrid, you still see, you know, huge parts of the city that are completely covered by graffiti and different forms of street art. And yet even there, I think there is some effort, as Skylar commented about the Chueca neighborhood, there is some effort to clean particular areas and make sure that people can’t express themselves in those ways. And so we see those struggles happening constantly around us.

Cathy, thank you so much for joining us today and sharing some of your work on stickers with us. We’re really grateful for your perspective, and we will make sure to direct our audience toward a lot of resources so they can dig more into this themselves on their own time. So thank you again.

Thank you, John. This was really, really good.