Exploring the Underground Graffiti Culture in Madrid

During my first hours in Madrid last January 2022, I started to notice that the streets, highways, walls, road signs, buildings, shops, metal shutters, and trains were all covered in graffiti. I was overwhelmed by the sheer amount of it as I saw names such as SMAK47, KISES, SUM, TOES, ZERF, FAS, T. ALTOIS, SODA anywhere I went. It is practically impossible to find a public space in the Spanish capital that has not been painted over. The city is literally covered in graffiti. I was intrigued to learn more about this form of self-expression and started digging through the internet. However, a simple Google search turned out to be misleading as most of the results showed examples of street art, not graffiti as you can see in the screenshot below.

Distinguishing graffiti and street art

Before elaborating on this point, I would like to acknowledge that graffiti is frequently referred to as street art, as the two often overlap. To convey my thoughts effectively and minimize the chance of confusion, I will view those terms separately and provide definitions that I think are most appropriate for the purposes of this article.

Encyclopedia Britannica defines graffiti as a “form of visual communication, usually illegal, involving the unauthorized marking of public space by an individual or group. Although the common image of graffiti is a stylistic symbol or phrase spray-painted on a wall by a member of a street gang, some graffiti is not gang related. Graffiti can be understood as antisocial behavior performed in order to gain attention or as a form of thrill seeking, but it also can be understood as an expressive art form.” So, the main difference between the two is that street art is usually done with permission while graffiti is illegal. As a result, graffiti usually manifests itself in the form of letters designed for quick execution while street art is an elaborate drawing that looks more like a painting.

The complex form and rich textures of street art would usually mean that artists have received permission to create their work. It is important to view these terms separately as they belong to two completely different, arguably opposing cultures which are somewhat in a fight with one another. I will dedicate a later article to explaining the rivalry between street art and graffiti in Madrid. A Milan-based art marketplace called Kooness further describes this contentious relationship between forms of what they call “urban art”. For now, I will provide a basic overview of the underground graffiti culture through sharing my personal experiences with locals.

Luckily, during my first month in Madrid, I was able to get to know a couple of graffiti artists who introduced me to their world. One Saturday night, I was walking back from a rave in the outskirts of Madrid together with a 22-year-old photographer. He asked me to stop for a second, pulled out his marker and started sketching something on the wall right in front of me. In less than five seconds he was ready with his tag. I was impressed by its aesthetics as it reminded me of an angle in an abstract way. There was something inherently creative and artistic that fascinated me, so I took a picture. If you look closely, you will be able to identify that the tag is made up of letters that spell ‘SODA’.

SODA tag in Madrid, Spain.

What is tagging?

Tagging refers explicitly to writing the artist's signature (or their pseudonym name or logo) on a public surface. This distinct signature is known as a tag, and the artist is referred to colloquially as a tagger. Tagging is the oldest and simplest form of graffiti. It is the backbone for basically all the other types of graffiti that developed through its evolution. It can be characterized as using only lines to form a signature hand style for a graffiti word. Whether it is with a marker, spray can, or a sharp object, it can be seen as a stylized writing of these letters.

A few weeks later I met up with SODA once again close to the Tribunal metro station. He needed to restock on spray paint, so we passed by a specialized store called Writers Madrid. They do a wonderful job at documenting graffiti culture on their YouTube channel, so I would recommend watching their videos. I will transcribe a poem from their documentary video about FAS in a future article, as I think it best summarizes the love artists have for graffiti and what pushes them to paint.

A complex, transnational history

When I asked SODA about his inspirations, he briefly went over the history of graffiti in Madrid. The first samples of graffiti appeared in the beginning of the 1980s during ‘La Movida Española’ – a countercultural movement that took place during the Spanish transition to democracy after the death of dictator Francisco Franco. Emerging from punk graffiti, native Madrid graffiti developed independently, with little knowledge of the existence of New York graffiti.

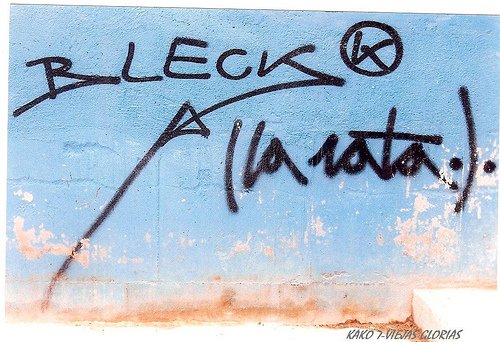

Muelle was the first graffiti artist in Madrid who pioneered the artform. His work was characterized by a line resembling the shape of a coiled spring ending in an arrowhead (you can notice the influence of the coiled spring on SODA’s tag). Muelle’s signature style lit up a whole genre, the “graffiti flechero,” which would then be joined by other artists such as Bleck and Tifón.

Madrid graffiti as we know it today originated in Philadelphia in the 1960s, but the most notable influences probably come from New York. The most common styles such as bubble lettering, throw-ups, and wild styling were adapted and are now dominating the streets of Madrid. SODA also draws influence from influential graffiti crews around the world such as 1UP, one of the most well-known crews in Berlin's graffiti scene that has developed a worldwide reputation. To summarize, SODA draws influence from the graffiti scene native to Madrid and is inspired by the groups and individuals that are actively contributing to the modern graffiti scene around the world.

While walking around the area, he would point out examples of his work to me. In the pictures below you can see variations of a throw-up (also known as flopeos or pompas) which is a slightly more complex version of a tag. It is perhaps the most common style of graffiti seen in the streets of Madrid. It is designed for quick execution (a couple of minutes or even seconds would suffice). With simplicity and minimalism in mind, characteristics of a basic throw-up include wide rounded letters, zero negative space on the inside, as well as one to two colors or just the outline, according to ArtRadarJournal.

This style originated in 1974 in New York. Around then, it was common for graffiti to cover the entire side of a subway car, and the works were becoming increasingly more sophisticated. LEE, whose work is pictured below, was one of the pioneers there, and his work is representative of the graffiti style that developed during that time.

NYC subway car painted by Lee Quinones. Photo: Eric Felisbret (1979). Retrieved April 15, 2022, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p030pgp0/p030pdns.

Another artist by the name of “IN” decided to take a different direction and focus on quantity. His logic was simple: by investing the same amount of time, effort, and paint that would be required for an entire wagon, he would instead produce hundreds of small throw-ups in various wagons, exponentially multiplying both the visibility and the durability of his work. This formula was quickly adopted by other artists, especially when the war on graffiti began in various cities. In a highly monitored and frequently erased environment, it was not worth investing time and materials into an elaborate work.

Despite the visual simplicity, a throw-up is considered to be one of the hardest forms of graffiti to master. It is also an essential for those who want to progress further into painting pieces, a larger and more complex form of graffiti.

Image source: Preguntas sobre el graffiti: ¿Cuál es el origen de los "flopeos" O "throw ups"? Urbanario. (2020, November 7). Retrieved April 15, 2022, from https://urbanario.es/en/preguntas-sobre-el-graffiti-cual-es-el-origen-de-los-flopeos-o-throw-ups/.

From throw-ups to pieces

A piece is perhaps the most evolved form of graffiti where nothing is off limits. This style provides the opportunity for artists to be as creative as they want, using as many colors, connections, shadows, characters, and add-ons as they want. Pieces can be easy and readable or complex, detailed, and unrecognizable. Pieces can be simple, such as in the following image, where the outline was painted with a spray can and the filler was made with a roller.

Other pieces, such as the following two examples, are more complex and elaborate, taking a couple of hours to make. The trio of styles that I've described - tags, throw-ups, and pieces - continue to form the basis of formal conventions of graffiti in Madrid today.

New developments

There have also been interesting contemporary developments in Madrid's underground graffiti culture. One new phenomenon happening in the Spanish capital is that several layers of graffiti are being painted on the same wall. This is because there is no more space to paint on ground level. I frequently see graffiti painted on top of other works on highways.

Image source: Google Maps Street View.

Graffiti artists are also forced to become increasingly more creative, so the use of ladders and rollers with extensions is starting to become widely adopted. Some writers even go to the extent of descending themselves from bridges with a harness. This pushes the boundaries of graffiti and results in the creation of new styles such as ‘pertica’ or ‘rodillo’.

I am fascinated by how graffiti artists like SODA express themselves by using the public space of a city as their canvas. Graffiti is not only an artform, it is also a lifestyle, a culture. Painting at night, breaking into train stations, exploring underground tunnels, running from police (hopefully not) are part of the everyday life of a graffiti artist. They go to great extents and risk their lives, careers, and freedom to realize their work. I have a lot of respect for those who keep this culture alive.