Interweaving with James J. Coughlin: The Roots of Racial Segregation in Buffalo, NY

Introduction: A Public Historian Digs Into Buffalo’s Racial Segregation

James J. Coughlin. (Photo courtesy of Mr. Coughlin)

Despite being the second largest city in the state of New York, Buffalo remains an understudied metropolitan area in US urban history. Nationally significant events in Buffalo have received fairly little scholarly attention: Buffalo was the first electrified city in the world (1896); Buffalo hosted a world’s fair in 1901, the Pan-American Exposition; and Buffalo was home to one of the most dominant National Football League franchises, the Buffalo Bills, who reached four consecutive Super Bowls and lost all of them (1990-1993).

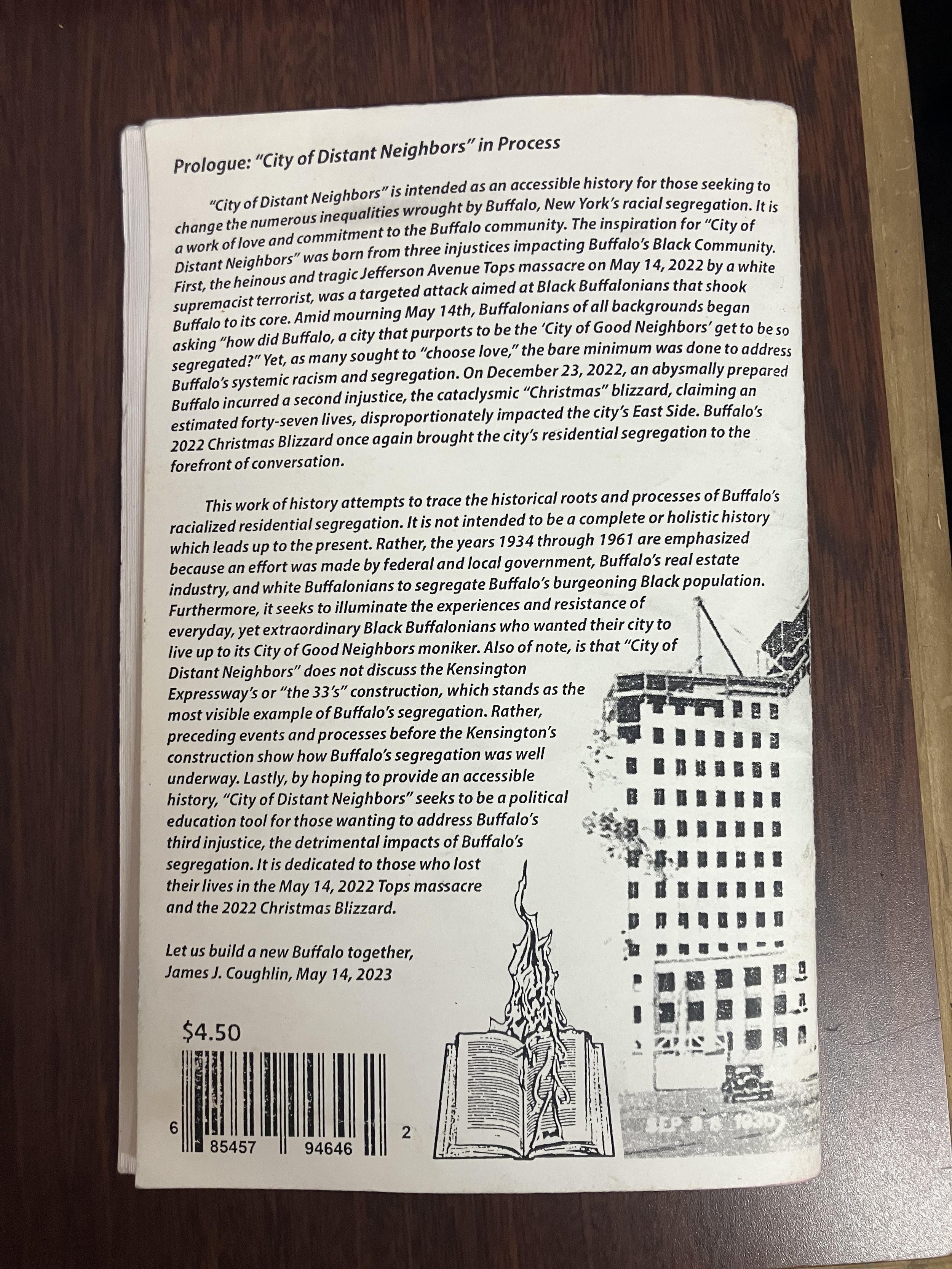

Public historians in Buffalo have attempted to fill the historiographical gap left by professional urban historians. One such scholar is James J. Coughlin, a Buffalo native. In May 2023, Coughlin published an important “zine” titled City of Distant Neighbors: The Proliferation and Entrenchment of Residential Segregation in Buffalo, New York (1934 to 1961), which Coughlin adapted from his Master’s Thesis, completed at the State University of New York at Buffalo.

In this brief 60-page study, Coughlin explores in detail the history of residential segregation of black and white Americans in the City of Buffalo between 1934 and 1961. The size of the zine belies its heft in research. A full bibliography at the end of the short history shows that Coughlin derived his claims from a wide variety of relevant primary sources, including government and planning publications, real estate company records, and the personal papers of city administrators. Coughlin also consulted contemporary articles in a wide range of media outlets.

James J. Coughlin’s May 2023 zine on the historical roots of racial segregation in Buffalo. (Photo: Burning Books)

Following this trail of documents, Coughlin reveals that US federal administrators, city government leaders, and the region’s real estate enterprises collaborated to redevelop the housing market during and after the Great Depression in a way that facilitated widespread home ownership for white Americans in racially homogeneous neighborhoods with a newly built, modern housing stock. These same actors colluded to restrict black American residents to the relatively undeveloped neighborhoods east of Main Street, where there was and continues to be a higher concentration of dilapidated houses and vacant plots of land.

In September 2024, I had the opportunity to meet Coughlin to discuss City of Distant Neighbors. Together we decided that his work was too important to review for Weave News without commentary from the author. Below, please find Coughlin’s reflections on the history of residential segregation of Buffalo and writing a zine that explains a huge part of the racial inequality so apparent in the city’s landscape.

SP: Who are the actors most responsible for residential segregation?

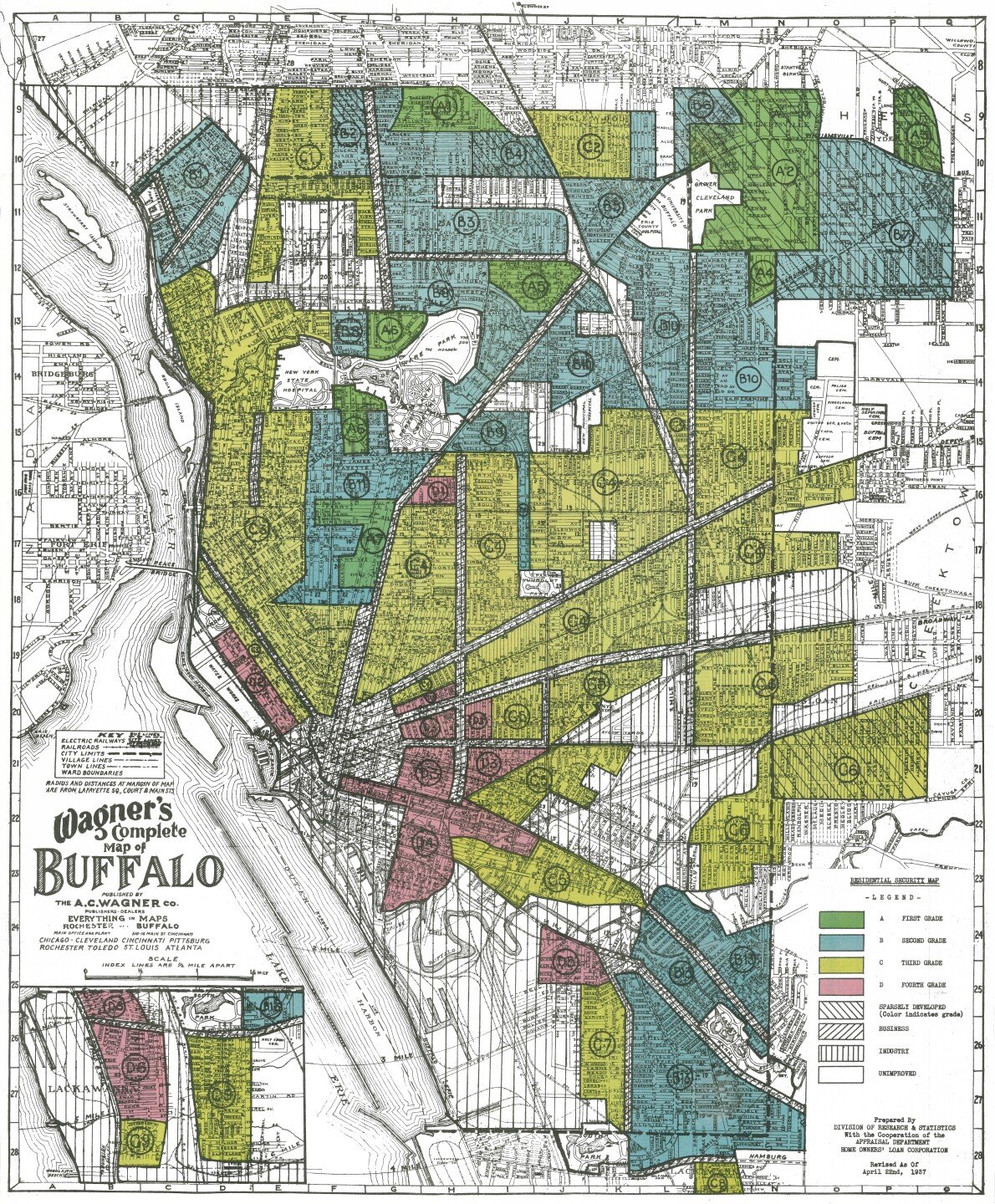

JC: When discussing Buffalo’s process of segregation, I describe segregation as an ecosystem, because numerous actors played niche roles in segregation’s broader structure and reinforced each other’s segregationist interests. Segregation was not inevitable. First and foremost, federal, state, and local government and elected officials gave legitimacy to segregation by instituting discriminatory housing policies such as redlining through the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and segregated public housing, such as the Buffalo Municipal Housing Authority (BMHA). These policies gave government assistance to white Buffalonians for opportunities to accrue wealth through homeownership while excluding and segregating Black Buffalonians. Segregation also limited Black Buffalonians’ political and economic power and their control over development in their neighborhoods, as demonstrated by the Ellicott urban renewal project.

A map illustrating the history of redlining in Buffalo. (Source: Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America)

Realtors, developers, and lenders also played a crucial role. When discussing these three actors, it is important to be cognizant of their economic priorities. Realtors want to find and create opportunities to make money while appearing friendly and professional. A group of realtors, such as blockbusters, sought to panic white households into selling their homes as Black households moved into their neighborhood. Simultaneously, developers offered these families opportunities to purchase newer and affordable homes in Buffalo’s periphery or suburbs. Developers intended that these neighborhoods, such as the Town of Tonawanda’s Green Acres neighborhood, built by developer Pearce & Pearce, remain white and used restrictive covenants to assure white households that their neighborhood would remain segregated and make the long-term commitment to purchase a home. Lenders would not invest in redlined neighborhoods East of Buffalo’s Main Street, such as the Ellicott and Masten Districts, where most Black households resided. The presence of Black households led to the perception that these neighborhoods were declining or “risky” investments. Rather, this lack of investment perpetuated a cycle of segregation and organized abandonment and prioritized the investment of mortgages and loans to white households.

“Residential segregation still has a negative impact on the quality of life for Black Buffalonians and is the root of most inequities which still exist. We have undoubtedly inherited and must grapple with the consequences of the history I discuss in City of Distant Neighbors. ”

White residents themselves also perpetuated segregation and reflected their own racial animus. A significant myth utilized was that Black households diminish property values and are unfit to be homeowners. This thinking stems back to America’s long history of white supremacy, and at the turn of the 20th century, ideas of Social Darwinism. Restrictive covenants placed the onus on white neighbors to protect each other’s property values and wealth. Tying into this are mainstream print media, such as the Buffalo Evening News and Buffalo Courier Express, which perpetuated and reinforced ideas of inherent Black criminality, a concern expressed by white households who ultimately contributed to Buffalo’s white flight.

How are these actors able to manipulate laws and public opinion to create segregation at the metropolitan level?

Redlining cannot be fully understood without analyzing the growth of realtors as a profession, and real estate boards such as the National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB) and Buffalo Real Estate Board (BREB). Realtors should be considered both as a group of business professionals and a group of political lobbyists. NAREB’s formation was an effort by realtors to gain trust and approval from prospective homeowners through the establishment of common business practices and ethics. Before redlining’s implementation, NAREB’s code of ethics forbade the introduction of Black households into white neighborhoods, to protect property values and maintain trust, thereby profiting off perpetuating white supremacy. Realtors’ practices transformed into government policies, as real estate boards assisted with the creation of redlining maps, popularized the notion that Black households reduce property values, and stoked white fears of neighborhood integration to turn “alarm into profit, and discrimination into dollars.” A Pearce & Pearce advertisement I found dated December 1955 advertised a minstrel show as part of the Green Acres clubhouse activities. Blockbusting, such as in Buffalo’s Fruit Belt neighborhood and the broader Masten District, and subsequent white flight, illustrate this process. Predatory slumlords purchased many of these blockbusted properties, charging exorbitant rents to Black households denied opportunities for homeownership.

1955 Pearce & Pearce advertisement. (Photo: James J. Coughlin)

A source I found significant was the BMHA’s self-published Ellicott Relocation: Objectives, Experience, and Appraisal. If I may quote my work, this study “surveyed 1,750 households that relocated from December 1958 through April 1961 due to the Ellicott renewal plan. Detailing initial plans to rehouse displaced households, Ellicott Relocation describes how increasing housing vacancies in surrounding census tracts within the Ellicott District, Fruit Belt, and Masten District ‘solved’ the housing crisis.” It's a telling snapshot of segregation’s forces interacting with one another, the state of Buffalo’s housing, and the language used to describe the process. Although where a majority of Black Buffalonians resided at the time, the Ellicott District was integrated, but also was Buffalo’s most overcrowded neighborhood with an inadequate housing stock. Despite this, Black residents had no say over the process and were displaced, and businesses and Black wealth were destroyed. Most Black households who relocated were renters. About 70% of households relocated in seven census tracts found in the Ellicott or Masten Districts. Contrastingly, most white households relocated either in North Buffalo, South Buffalo, or Buffalo’s suburbs. The BMHA’s study also indicates that fifteen realtors working with BREB assisted relocating, or rather, steering families. Instead, the Ellicott Relocation Study defines this process as “natural market forces” which is a colorblind, race-neutral way to say “a self-fulfilling prophecy and the culmination of Buffalo’s housing segregation.”

Why did this happen when it did, 1930-1970?

Demographically, Black Buffalonians were only 3% of Buffalo’s population until 1940. Economic stimulation brought upon by World War II caused employment shortages in northern industrial cities such as Buffalo, which were filled by African Americans who migrated north during the second great migration. By 1970, 20% of Buffalo households were Black-led. The FHA’s redlining policies began during Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency as part of his administration’s efforts to get the United States out of the Great Depression by making home ownership more affordable than ever before and only accessible to white households. Government backed loans and the criterion established also reduced the risk for lenders. Following World War II, there was a housing shortage in Buffalo and nationwide, and lenders were more than willing to invest in home construction through FHA backed loans. Realtors and developers also shaped the parameters of government backed investment. Along with their lobbying and creation of redlining maps, suburban developers influenced how suburbs would be designed and which residents would be included and excluded.

“Deconstructing residential segregation means deconstructing the structural forces and barriers that uphold it. Doing so should guarantee resource equity and access for all residents, rather than hoarding resources, investment, and wealth in predominantly white neighborhoods. More resources and education need to be devoted towards fair housing to ensure prospective renters and homeowners are not discriminated against or restricted by seemingly colorblind barriers. ”

Public housing’s implementation and growth also plays a substantial role. FDR’s Secretary of the Interior, Harold Ickes, and public housing agencies adhered to the neighborhood composition rule that public housing should “reflect the previous racial composition of their neighborhoods.” Following this lead, BMHA’s construction and managing of the Willert Park Courts was segregated and reserved for Black households, while other public housing built throughout Buffalo was reserved for white households. The 1930s also represented a nationwide shift in defining “whiteness,” which broadened to include Southern and Eastern Europeans. Although white Buffalonians still strongly maintained their ethnic and cultural identities, whiteness determined who reaped the political and economic benefits of the New Deal, such as access to homeownership and resources, justified through excluding African Americans. The Buffalo Public Housing crisis of 1941 and 1942, which resulted in an expanded and segregated Willer Park Courts, shows white neighborhoods in North Buffalo and Kenmore, Lovejoy, Cheektowaga, and South Buffalo, organizing against neighborhood integration, purporting the necessity to protect property values and respective communities.

Alongside suburbanization is the growing use of automobiles for suburbanites to commute from their homes to Buffalo quickly and efficiently. This ushered in a period of urban renewal projects that sought to benefit commuters and “revitalize” the downtown area. In reality, urban renewal led to displacement for Black Buffalonians, evidenced through the Ellicott Urban Renewal Plan and the Kensington Expressway’s construction which facilitated or reinforced segregation already in place.

What are the implications of your study for today? Is this still happening?

Residential segregation still has a negative impact on the quality of life for Black Buffalonians and is the root of most inequities which still exist. We have undoubtedly inherited and must grapple with the consequences of the history I discuss in City of Distant Neighbors. Analyzing Buffalo’s segregation cannot solely focus on the city of Buffalo but rather throughout greater Erie County. Approximately 85% of Black Buffalonians live East of Buffalo’s Main Street. Only about one-third of Black-led households own their home in Erie County compared to about 70% of white-led households. East side neighborhoods have comparably higher rates of air pollution, environmental toxins, and lead poisoning. This has also led to shorter life expectancy and higher rates of asthma and cancer among Black Buffalonians. Food apartheid, exacerbated by the May 14th, 2022 Tops Massacre, is an ever-present reality. Consequently, most Black Buffalonians live in older housing stock as tenants. Although Buffalo has a proactive rental inspection law that seeks to protect Buffalonians from the impact of its older housing stock, this is woefully underfunded and has not sincerely addressed the broader consequences of redlining and disinvestment from segregated neighborhoods.

The back cover of the zine. (Photo: Steve Peraza/Weave News)

Housing discrimination still impacts Black Buffalonians seeking to move into a suburban neighborhood. Many landlords refuse to accept section 8 housing choice vouchers and other lawful sources of income or do not maintain their homes in a condition where government rental assistance would be applied following an inspection. Discrimination on this basis is illegal in New York State and Erie County. Secure homeownership is still dubious for Black Buffalonians, who were disproportionately impacted by the subprime mortgage lending crisis in 2008 (see Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law) and ongoing discriminatory lending practices in East Side neighborhoods, as reported by State Attorney General Letitia James. Newer employment opportunities in Buffalo’s suburbs are out of reach or take longer to commute to for residents in segregated neighborhoods. Segregation is also impactful in the Buffalo public school system, and most consequentially, in the amount of funding per student in Buffalo compared to suburban school districts. The University at Buffalo’s North Campus construction in Amherst without a direct route of public transportation also prefers suburbanites with vehicles. Gentrification resembles previous urban renewal plans by displacing neighborhood residents, developers speculating on the value of land, without consideration of the needs of residents already living in gentrifying neighborhoods. I encourage folks to read Henry Louis Taylor, Jr.’s 1990 study and 2022 follow up, “The Harder We Run,” which meticulously outlines ongoing disparities and inequities wrought by Buffalo’s segregation.

What can residents do to integrate the metropolitan region of Buffalo?

Deconstructing residential segregation means deconstructing the structural forces and barriers that uphold it. Doing so should guarantee resource equity and access for all residents, rather than hoarding resources, investment, and wealth in predominantly white neighborhoods. More resources and education need to be devoted towards fair housing to ensure prospective renters and homeowners are not discriminated against or restricted by seemingly colorblind barriers. Income requirements and credit score requirements either unreasonably limit or disparately impact Black and Brown renters from having access to suburban neighborhoods. Housing Opportunities Made Equal (HOME) ensures fair housing enforcement and that housing is available in the neighborhood of a household’s choosing. Growing public transportation, particularly through expanding the metro rail train and constructing other train lines would ensure segregated Black Buffalonians have access to resources regionwide. Accessible and healthy food also needs to be seriously addressed and reckoned with.

Numerous activist groups are addressing Buffalo’s residential segregation at the grassroots. The Fruit Belt Community Land Trust sought for residents to own the land their homes are built on to stem gentrification’s tide and ensure community autonomy over their neighborhood. The East Side Parkways Coalition has been organizing against a billion-dollar boondoggle proposed by the New York State Department of Transportation to cap a part of the Kensington Expressway and restore the former Humboldt Parkway, without remedying the expressway’s and broader neighborhood’s environmental and health ramifications. This committed group of activists wants to ensure urban renewal’s mistakes are earnestly addressed with community input by asking ‘how may East Side residents dictate funds being devoted to their neighborhood are used to address root causes of harms rather than continue perpetuating them.’ Black Love Resists in the Rust, in addressing harms perpetuated by local policing and incarceration, have initiated their “No New Jail” campaign against a proposed $200 million county jail. Similarly, they have asked how may this proposed funding go towards addressing the genuine public safety needs and harms perpetuated by residential segregation.

Participatory budgeting has been encouraged to democratize and determine by the people who fund these projects how their money should be spent. Imagine that! According to Partnership for the Public Good, approximately 8,000 vacant lots are owned by the City of Buffalo. To avoid the harmful impacts of yesterday’s urban renewal and today’s gentrification, determination by residents of segregated neighborhoods is essential for stewarding a better future, rather than developers and speculators. There is no one, simple answer, but multiple ways for everyone to be involved in addressing and repairing harms wrought by segregation.