The Deepest Fake News: Project Introduction

Dedication

This project is dedicated to four courageous individuals whose lives and work have made a direct impact on the struggle to make settler colonialism visible, center the voices of the colonized in public discourse, and build a more just world for all. Two of them paid for this work with their lives.

Research for this series was carried out under the auspices of the Piskor Faculty Lectureship at St. Lawrence University and was originally presented at the university in April 2022. The contents of that lecture have been modified slightly for this web series. I am grateful to the university for its support of the project. I would also like to give special thanks to Marina Llorente and to my colleagues in the Global Studies department – the best intellectual home one could possibly hope for.

Beyond acknowledgment

As a professional teacher/scholar, I work at a university that sits on land that became part of the United States through a process of settler colonization. Land acknowledgments often made at the start of public events are designed to put this issue on the table in some basic way. The acknowledgment typically offered at my home institution, for example, emphasizes that the university “occupies the traditional lands of the Haudenosaunee Nations” under a diplomatic relationship that began with the Canandaigua Treaty of 1794.

But a structural reading of historical and contemporary realities reveals that such gestures are fundamentally incomplete. Among other things, standard land acknowledgments rarely acknowledge that white settlement produces intergenerational trauma for native people and generational wealth for settlers – wealth that is the lifeblood of institutions like mine.

As someone who continues to benefit in innumerable ways from the ongoing settler project, I am under no illusion that my acknowledgment of these realities amounts to more than empty words. But for the record, I want to state that for me, colonization demands decolonization – and as Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang famously argued in a 2012 article, decolonization is meant to be material, not just metaphorical. At a minimum, I hope that this series will help enlarge the space for discussion on mine and other campuses about how we are all implicated not only in the colonial past, but also in the colonial present.

Settler colonialism, “here” and “there”

Let’s begin with two examples that may seem unrelated.

First, when Palestinian refugees of all ages rose up in March 2018 in a mass mobilization near the wall that enforces their mass incarceration in the Gaza Strip, their framing of the mobilization as the “Great March of Return” provided a challenge for journalists. After all, establishment media coverage of Palestinian protests is typically organized around a set of normative categories that assume the existence of the state of Israel, its monopoly on the legitimate use of violence, and the desirability of “peace” (defined implicitly as the absence of Palestinian resistance to Israel’s colonial project).

The Great March of Return, Gaza/Palestine, March 2018.

(Photo: UNRWA)

But the people in Gaza were not mobilizing for “peace.” They were mobilizing for “return.” Return to what? Exploring that question fairly would have required journalists to acknowledge that the place they call “Israel” is in fact a construct representing an ongoing project of removal, erasure, and elimination – that is, a project of settler colonialism. The only way the state of Israel could have come into existence as a Jewish-majority state is through the removal of Palestinians from the land – the land to which the refugees in Gaza were (and still are) demanding to return.

Yet as we will see, the concept of settler colonialism played no role in establishment media coverage of the Great March of Return.

To understand why this absence matters, let’s listen to Palestinian-Canadian scholar Mark Ayyash, speaking with me on the Interweaving podcast in March 2020:

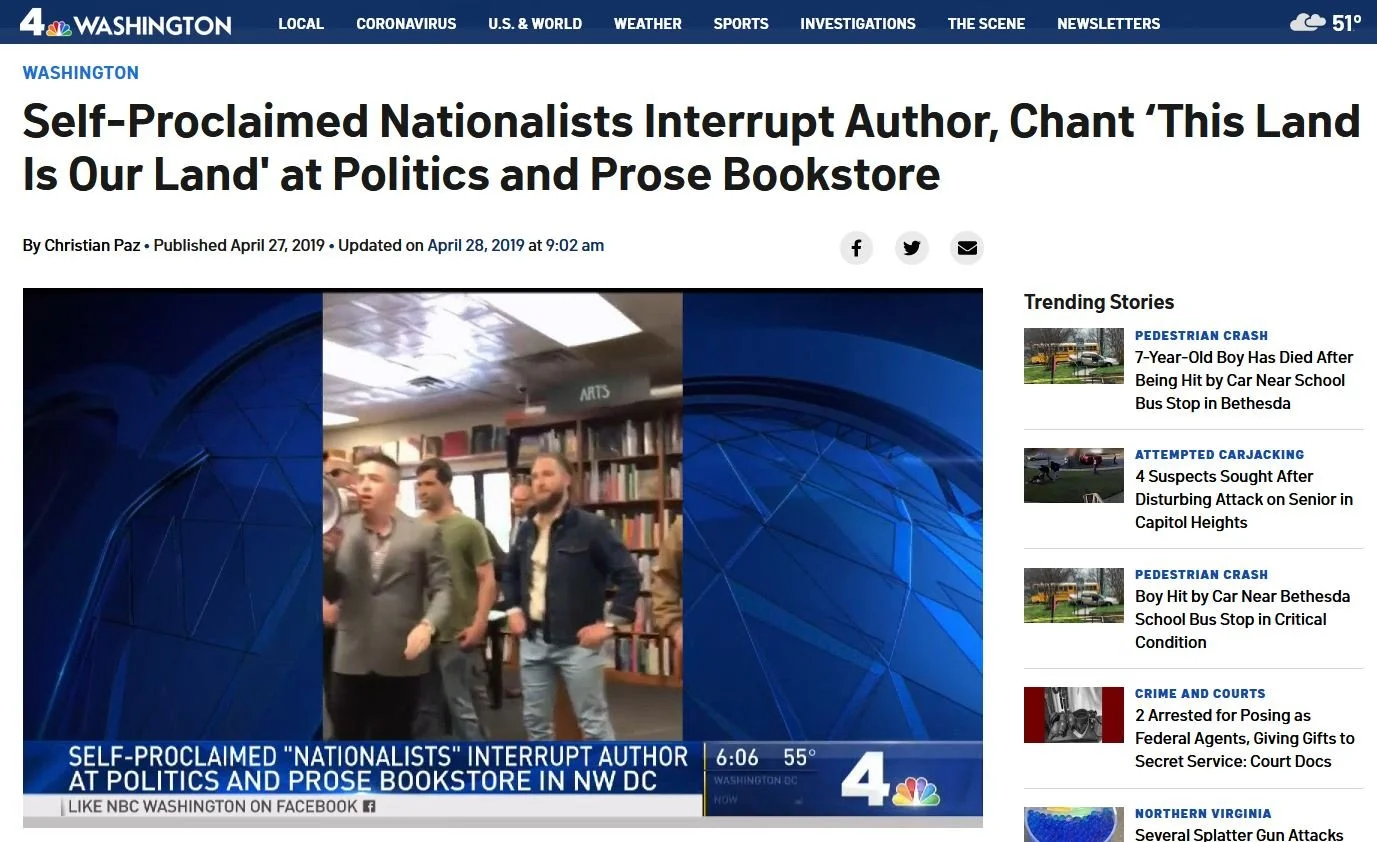

And now a second example: In April 2019, a book event in Washington, DC, was interrupted by a group of white nationalists chanting, “This land is our land!”

NBC Washington report on white nationalist disruption of author presentation of the book Dying of Whiteness: How Racial Resentment is Killing America’s Heartland, Washington, DC, April 2019.

Coverage of the incident sought to distance the obviously racist protesters from the presumed normality of a liberal, multiculturalist consensus – a consensus that has long celebrated Woody Guthrie’s iconic “This Land Is Your Land” as an anthem of patriotic inclusion. Yet Guthrie’s song can also be read – against itself, admittedly – as naturalizing the ongoing settler project carried out on the ruins of many of the indigenous nations of “this land.”

Here I am reminded of Ghassan Hage’s sharp observation that even in Australia, where there is no significant movement for aboriginal sovereignty, white “paranoia” over colonial history remains a potent force – a force that manifests itself in ongoing debates over multiculturalism.

In this light, we see that the distance between the white nationalists and the liberal multiculturalists may not be as great as we thought. Both, after all, are beneficiaries of the settler project. The difference is that while the white nationalists openly celebrate their status as settler-colonizers, the liberals would prefer to keep that common history hidden from view.

These two examples reveal a fundamental disconnect that lies at the center of this project: a disconnect between the importance of settler colonialism in scholarly and activist arenas and its relative absence from everyday news narratives and the public “conversation” they influence.