Dissecting Boston VIII: Land Addiction

Introduction

The Trump administration has moved to open public land, national monuments, to private investment. The borders that protected public domain are unraveling, soon to be replaced by the private lines of corporate capital. It is here where borderlines collide. From the black snake of DAPL to the border fence with Mexico, the outlines of a global catastrophe are retraced, penned in the blood of future generations. The privatization of land, a fundamental American commodity, lies at the center of this addictive division. As Winona LaDuke so aptly stated, we are dealing with an addict. The addict she was referring to is the fossil fueled economy. There is another addict that proceeds this derisive construction. We are dealing with an irrational society, addicted to ownership. Own the fuel, own the land, own the world. This society, systemically violent structure, believes that it owns all of us. Our personal lives are owned by Facebook, our political affiliation by Twitter, our memory by Google, our vital energy by Starbucks, our mobility by Exxon, our culture by Disney and our country by Goldman Sacks. Our backyards are their playground, open for an addict to frack.

Are we complicit in these entwined borderlines of private capital? Certainly.

In this blog post I will continue to use (note the term of ownership) the case study of Plum Island to explore how borders are employed to structure the identity of a place and its inhabitants. As noted in the previous blog post, ownership is illusive. It can be be washed away by the tides of human induced disaster. The ownership of land is sustained be the violence of exclusion, displacement. The land “theft” that is currently being exhibited in the West Bank, was first tested on the land where most Americans now stand. Yet this sense of ownership has become unsustainable. When you own, you are given the right to exploit. When the exploited commodity disappears, you are left dangling over open ocean. This process occurred on the beach of Plum Island, where different forces battled ideologically and consirvation was used in the name of commodification.

"Fence" by Tzintzun Aguilar-Izzo

“Favored by Nature, Unspoiled by Man”

The economic metropolis of Boston has for centuries exported tourist, seeking to escape the churning wheel of capital. The tourist established vacationland colonies, slivers of a privatized paradise. Plum Island has long been one of the destinations of New England voyeurism. Throughout the centuries, descendants of the first English colonizers have profited from the commodification of wide beaches and salty air. The first European inhabitants of the Island, hoggs and catlle were themselves commodities; commodities that were soon expelled from the Island due to their destructive presence on the delicate sand dunes. Now most of the northern part of the Island has been cut up into small squares, a 1920s resort that is slowly being stolen by the ocean. The ocean doesn’t comprehend the conception of private property.

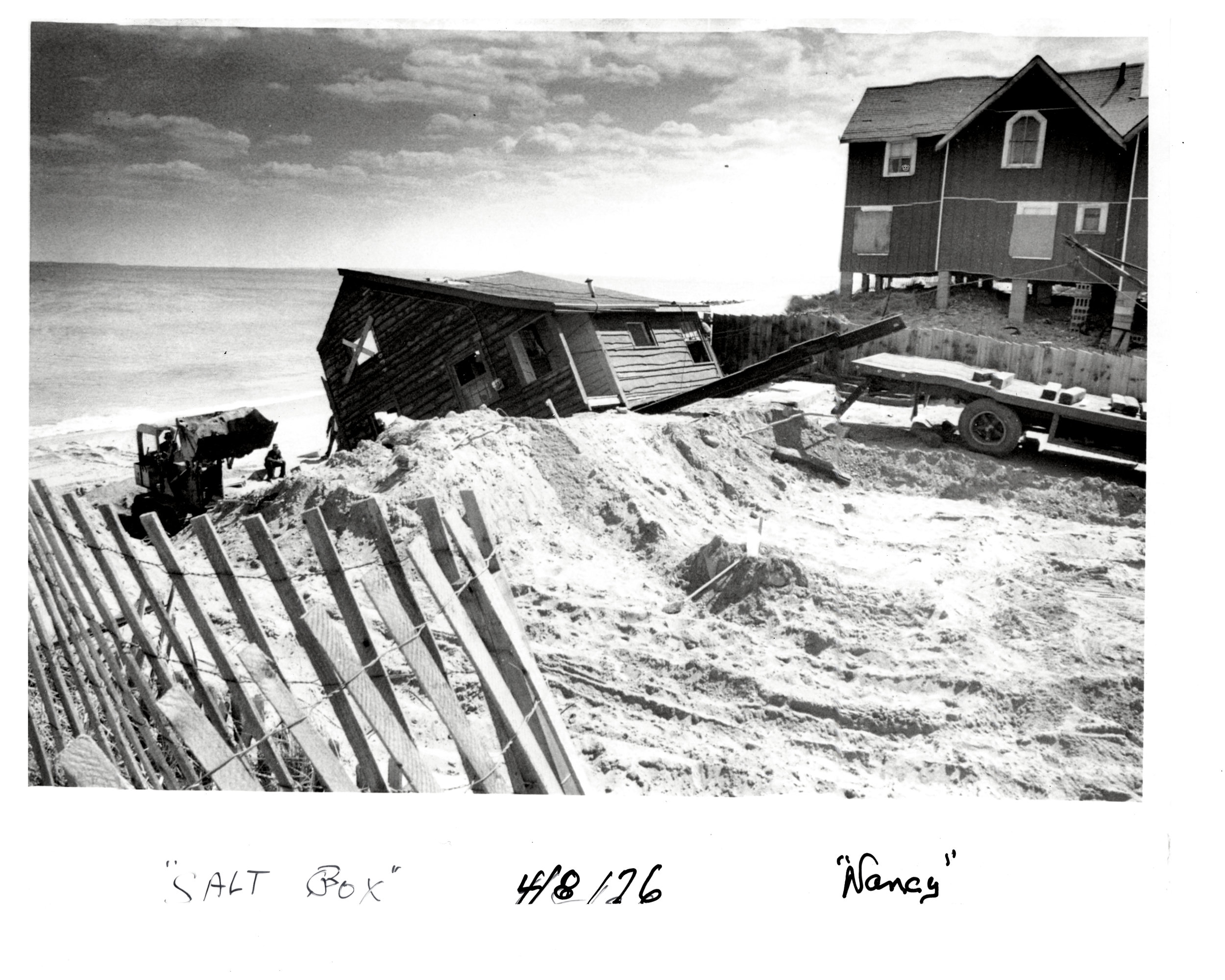

"Salt Box." Newburyport Public Library Archival Center

Plum Island itself is a barrier Island, protecting the mainland from the gales and high waves of tumultuous winter storms. The Island has undergone constant transformation. At various points in time, the colonizing landowners of Plum Island suffered the confusing dilemma of owning a free flowing body of sand, constantly expanding and contracting. The Pettingills saw their private property increase exponentially between the years of 1840 and 1850 (Wear 7). Their fraction of the Island grew, due to a series of harsh winter storms, which in 1839 ripped off portion of the Salisbury Beach (7). E. Moody Boyton, who had previously acquired his property from the Salisbury Beach proprietors, sued the Pettingill heirs (7). He claimed that the Petitngill's newly acquired land was in fact his private property. In the end, the Pettingill family retained their newly acquired “North Point,” and the courts sided in their favor, “citing an old Massachusetts law that gave such accreditations to the owners of the land to which it was added” (8).

If you walk along the shores of the old Pettingill's North End, you will find large portions of sand dunes that have been washed away, obliterated. The houses, once protected by small hills of sand and “sand lovers,” are now dangerously close to a watery end. The fences that corral people to the beach, keeping their destructive feet off the delicate sand dunes, are now left landless; they are suspended above cliffs of sand and dangle in the ocean waves. Besides small portions of the old Pettingill land that was turned into a state park, the Pettingill land has been divided into numerous small squares: fenced in, partitioned, cubicles of private property. These land parcels hold million dollar houses, million dollar sections of transitory luxury. Despite global warming, Plum Island has always suffered constant transformation. As new houses continue to be built, beach cottages remodeled to palaces, investment is being poured into a vacationland that in the near future will become uninhabitable.

"No" by Tzintzun Aguilar-Izzo

In the 1920s, the heirs of Moses Pettingill sold their land, and the “deeds were transferred from the Pettingill heirs to J. Sumner Draper of Milton, and from him to the new Plum Island Beach Company and the United States Government” (“Plum Island Deed Recorded” 1). The Unites States Government has long battled this transfer of land. At the time, the state representative Mr. Emery, stated that the “commonwealth of Massachusetts may have claims to all that part of the Island cause by the shifting mouth of the Merrimac river” (“For State to Take Plum Island” 1). While the argument once again hinged on the fluctuating nature of Plum Island, their aim was to protect the beach from over-development. They intended for Plum Island to be a resource for all residence of the area, not just a select few of private landowners. In the end, despite the government’s best efforts, the Plum Island Beach Company (a Boston owned corporation) prevailed. To this day, the public vs. private debate continues. Most the Island has been transferred from private ownership to public domain. It is the old Pettingill land, the very north of the Island, that has been sliced up by the Plum Island Beach Corporation.

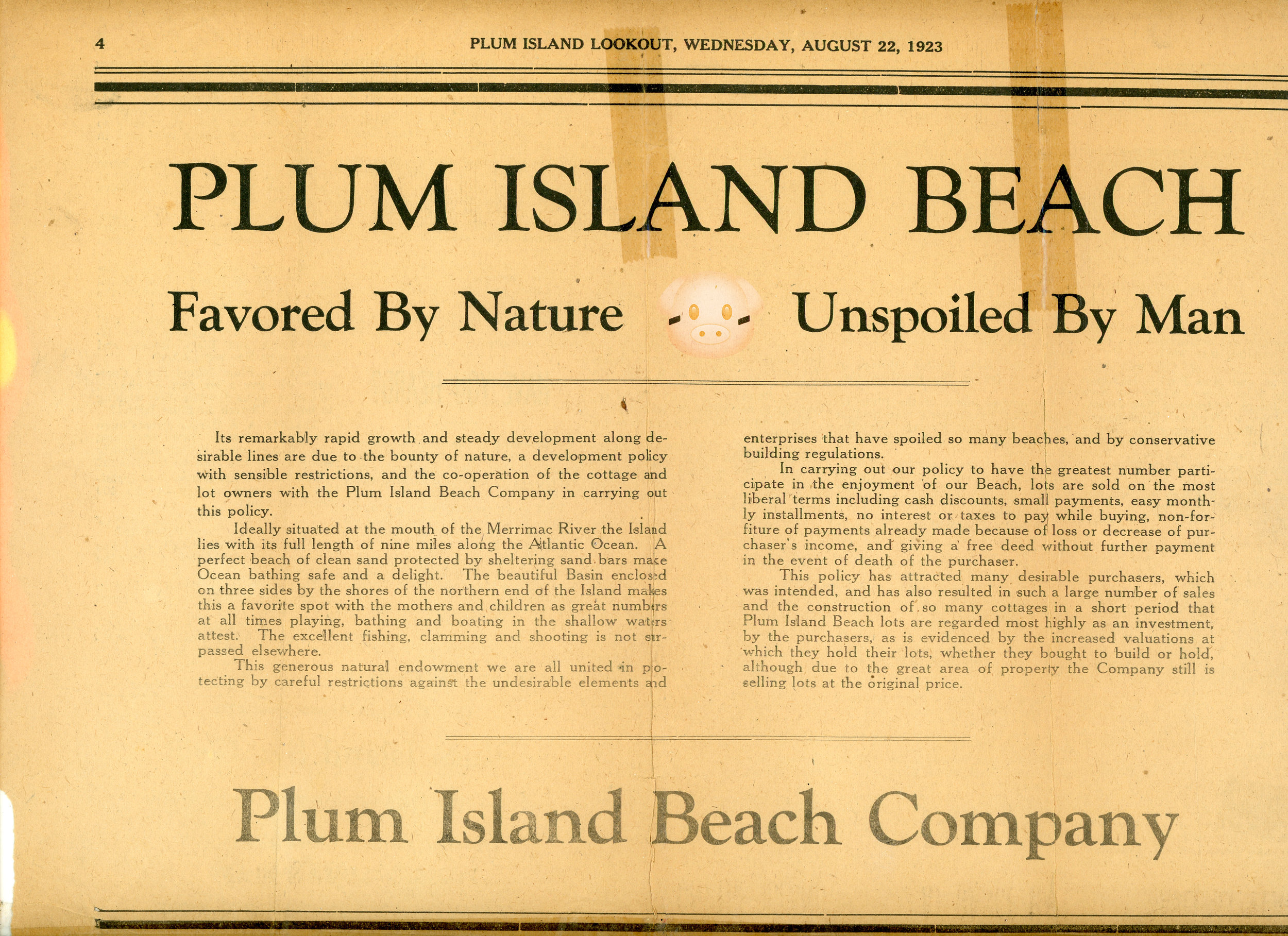

“Unspoiled by Man, Favored by Nature.” Plum Island Lookout 23 August 1923: 1. Print."

The Plum Island Beach Co. rapidly moved to maximize their profits. Their development of the Island was deemed “aggressive” by many of the Island’s previous inhabitants. The corporation claimed that “under their management and ownership of the Island will be much finer place to live than it ever has been” (Wear 23). They claimed sole ownership of the northern part of the Island. It was their Island, and thus they were at liberty to build a “paradise” in their image. They also commenced heavily advertising Plum Island, slowly developing its iconic presence and cultural topography. In their local newspaper, entitled the "Plum Island Lookout," the Plum Island Beach Co. positioned itself as the saving presence that protected “this natural endowment” and had the authority to place “careful restrictions against undesirable elements and enterprises that have spoiled many beaches (...) (Plum Island Lookout 1). They sought to develop the Island as a “place at the seashore, easily reached, and with plenty of room for my children to romp about, and where the land is likely to grow in value” (Plum Island Beach Brochure). They marketed their lots as commodified partials of “unspoiled beach,” perfect for people that don’t like “dress up places” or so-called amusement resorts” (Plum Island Beach Brochure).

"Private" by Tzintzun Aguilar-Izzo

What Is to Come

In the following post I will continue elaborating on my research, and explore the beach loving community cultivated by the Plum Island Beach Co.. I will then trace this conception of ownership to Plum Island’s current real estate environment. The current population of Plum Island was consciously developed, and marketed. These divisions were strengthened by a population addicted to paradise. Much like the fossil fuel and coal economy, the addiction to paradise lead to blind and irrational decisions. To a certain degree, most “first world citizens” are addicted to a precise portion of global warming. Does that mean we are all addicted to the concept of owning?

...

Special thanks to the Newburyport Public Library Archival Center staff for their endless patience and generous assistance in helping me dig deep into Plum Island’s history.

“For State to Take Plum Island: Senator-Elect Emery Files Bill to Secure Legislative Action.” Newburyport Daily News 27 December 1919: 1. Print.

“Plum Island Beach Brochure.” Newburyport Public Library Archival Center, Newburyport, Massachusetts.

“Plum Island Deed Recorded: Final Act in the Transfer of Shoreland to the New Beach Company.” Newburyport Daily News 10 February, 9020: 1. Print.

“Unspoiled by Man, Favored by Nature.” Plum Island Lookout 23 August 1923: 1. Print.

Weare, Nancy V. Plum Island: The Way It Was. Newburyport: Newburyport Press, Inc, 1993. Print.