Dissecting Boston XI: Vandal Art

Stickers, plastic, paper, pasted on surfaces, covering, hiding, revealing.

In my previous Weaving the Streets blog post, I described my most recent act of sticker resistance. To complicate and irritate the act of cultural masking, I placed a sticker on a taco food truck on Plum Island, Massachusetts. The sticker was small, barely visible. The action wasn’t meant to be viewed by the public. Its desired audience were those guilty off appropriating Mexican heritage and social justice movements for their own financial gain: the food truck owners.

A day after I placed the sticker, the food truck was removed, and parked elsewhere. Was my action effective? For the moment, this question is left unanswered. However, there is an even more pressing question. Can small acts of artistic resistance truly unravel the borders that divide our actuality?

In this series, I strove to dissect the borders that lie underneath the surface of New England’s cultural topography. At this point in time, when I have almost completed my research and actions, it is necessary to lay bare my personal artistic/activist methodology. Devoid of context, my acts of artistic resistance can be misinterpreted as pointless vandalism. It is thus necessary to clarify my artistic/activist process. I will reveal previous invasions I have undertaken to unmask the silent voices, press the unmute button of history.

In this blog post I will reveal a series of actions I have conducted within the border-walls of the museum. Museums are also fragmented by their own borders: white dividers of culture and history. They legitimize existing structures of power. They frame our conception of reality, and exclude the voices that contradict the status quo. Museums, like most institutions of learning, tend to recolor the surface of history. They paint over the subaltern voices of alternate actualities.

The list that follows isn’t a recipe. It is series of actions, that have evolved exponentially. Many of these attempts can be seen as failures. Yet, they can be employed as platforms from which to unleash future actions.

Reflections of visitors in "China: Through the Looking Glass" (2015), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

Previous Actions

During the Montreal Biannalle (2014-2015), the artist Abbas Akhavan planted corpses of animals throughout the entire exhibition. The taxidermied animals were installed throughout the gallery. They resembled the roadkill of a society ignorant of the "fragility of life." By placing the animals amongst inorganic art pieces, the safe viewing space of the museum was shifted.

These animals functioned as an intrusive invasion in the museum. Hidden within the corners of the visitor’s tunnel vision they were "a call to empathy." Yet their placement within the white walls of the Montreal Biannalle (given the official level of acceptance by the art institution) formalized the animals as mere art objects. These "doubly dead" signifiers have been frozen for eternity in a museumified state.

The Biennial goer payed to see these carcasses. Thus, they also functioned as attractive decorations, filling the space of a sophisticated tourist destination. My action consisted of surreptitiously placing rubber ducks beside the dead corpses. By planting a triply dead piece of plastic beside the "double dead" corpses, I questioned their use as signifiers of "fragility." Because of the nature of my actions, I decided not to document my intrusions. I felt this would solidify my actions within the museum space, and institutionalize my acts of rebellion.

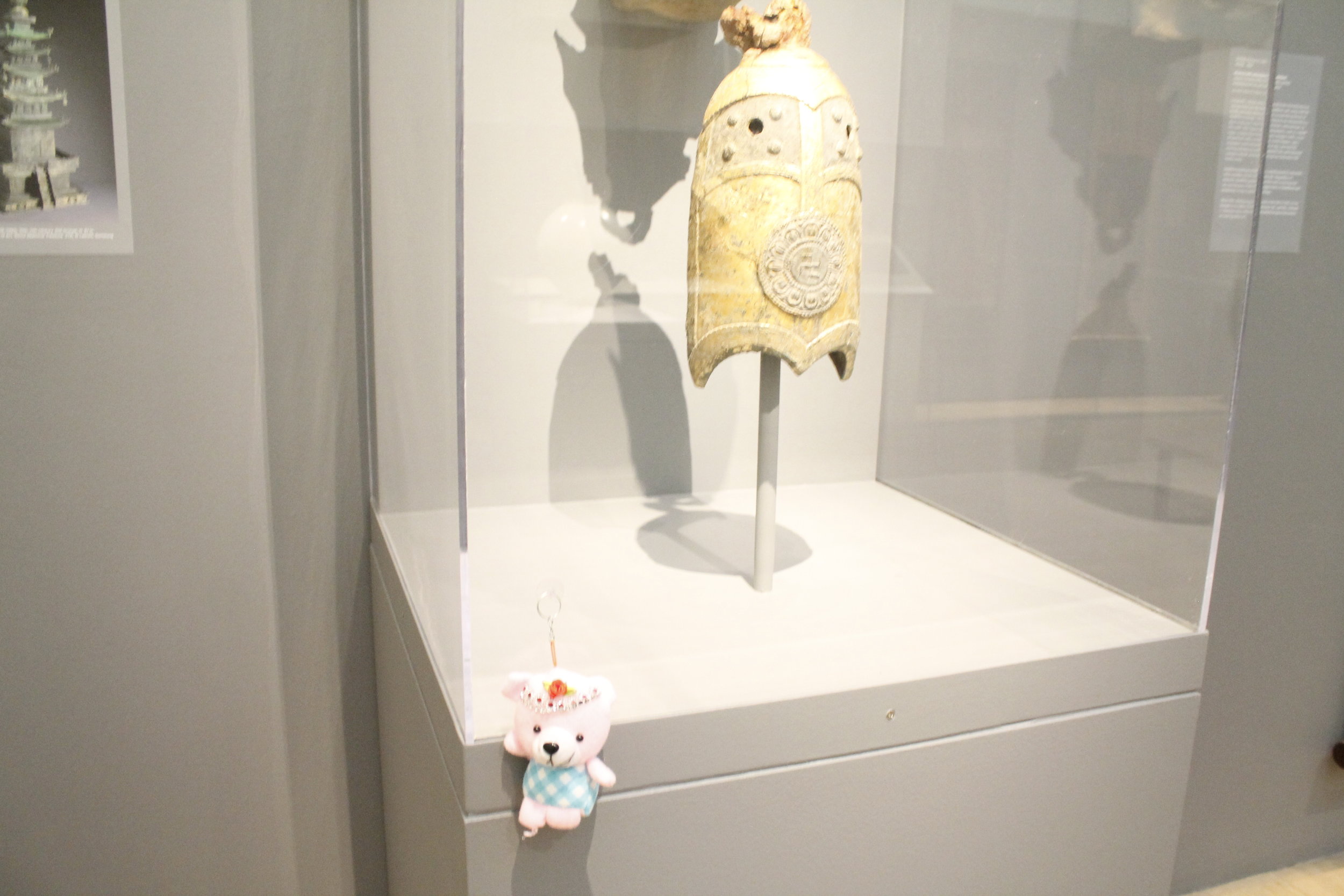

Documentation of the Invasion within "China: Through the Looking Glass" (2015).

I undertook a similar, yet more sophisticated action, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The exhibition I intruded was "China: Through the Looking Glass" (2015). The world of fashion appropriated the East Asian wing. The cultural art objects became the backdrop for manikins dressed in Asian themed "haute culture and avant-garde ready-to-wear [...]" (MET Pag 3). The museum stated that Orientalism is a "two-way conversation, a liberating force of cross-cultural communication and representation". The curators, as well as their corporate (Yahoo) and private Chinese founders, presented the argument that art isn't the platform on which to have politically charged conversations. Art is “all about harmless surface and shine" (Cooter NYT).

Documentation of the Invasion within "China: Through the Looking Glass" (2015).

The art on display "is reduced to being a display in a fashion shoot," an empty signifier, relieved of its cultural context. Chinese culture and history became a literal costume, a fetishistic mask. To remove this mask, I participated in the masking process. Pink teddy bears in tutus appeared, attached to the glass cases. Culturally unspecific, gendered pink, and fetishized in the clothes of a thirteen-year-old dancer, these kitschy objects served to further spectacularize this already superficial representation.

Documentation of the Invasion within "China: Through the Looking Glass" (2015).

Working from Within

In 2015, I became a Visitor's Assistant at the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston. It was an opportunity to observe a location which I had experienced as visitor, tourist, and museum vandal. I became part of the museum's infrastructure. I was one of the invisible people who helped coordinate the visitors’ experience. While I considered this position a source of income, I used it to penetrate the unseen factions of the museums infrastructure. My previously constructed irritants were superficial critiques. They were aimed at the act of invisible exclusions, but they didn't truly question the normalized networks of the museum experience.

I decided to undertake a more profound invasion. One that was based on a carefully orchestrated study. The subjects of this pseudo-ethnographic study were my own perceptions of my world view. As I was working directly within these networks, I underwent the rigorous process of acquiring the skilled vision of the museum's most visible employee.

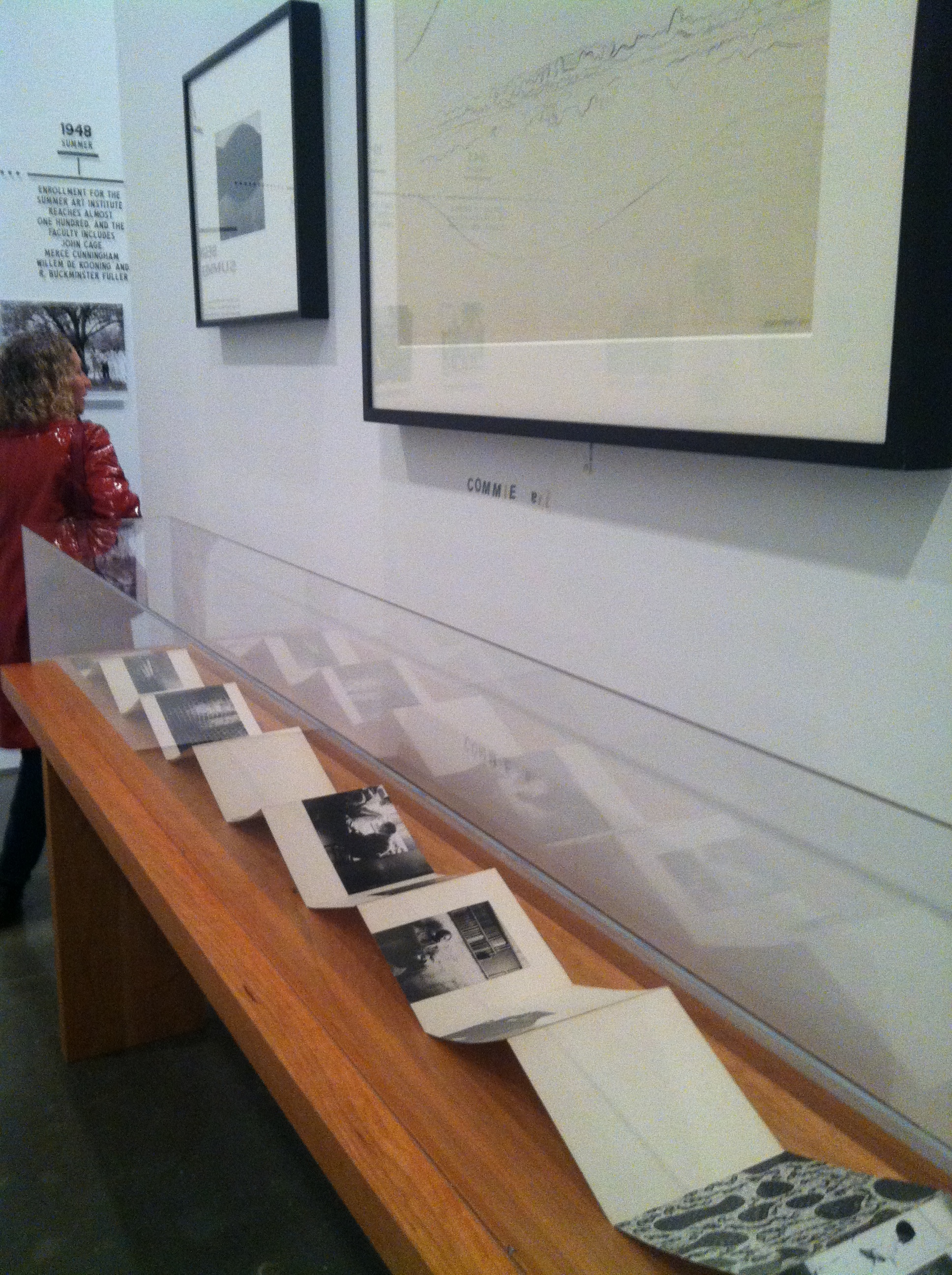

I focused my research, critique, and subsequent actions on"Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933 - 1957" (2015). The exhibition was one of the largest ever held at the ICA/Boston. For this reason, they hired several special exhibition employees, myself included. While extremely innovative in its presentation, the exhibition focused on an area of history that was normally outside the temporal spectrum of contemporary art museums: the modernist foundation of the contemporary.

Surprisingly, while the museum centered the exhibition around the artwork made by the professors and students at an extremely progressive liberal arts college, it silenced the political context in which the artwork was created. As a Visitor Assistant, I was trained to recite the college’s history. I was supposed to tell a censured version of an experimental fusion of collaboration, education and social structures.

The task I undertook was to re-politicize a history that had been reduced to the shapes and colors of an out of context abstract expressionism. The museums narrative fluctuated, as it avoided any references to the political leanings of the college students and professors. When describing how BMC finally closed, they portrayed a quasi-romantic process of inevitable decay. No historical process is that tidy, no story ends so elegantly.

I conducted my own investigation into the matter, and I came across an FBI document, detailing their investigation of BMC. According to a letter written to the director of the FBI, the "Veteran Administration officials have taken steps which have resulted in the school's approval by the State Board of Education of North Carolina being withdrawn, thus cutting off subsistence of veterans" (FBI 1956:2).

A number of World War II veterans went to BMC, and their GI bills were one of the last lines of cash keeping the school afloat. According to the FBI, BMC was a very "unusual type of school, for example, the student may do nothing for the entire day and in the middle of the night, may decide that he wants to write or paint [...]" (FBI 1956:2). By referencing that the school was "unusual" the FBI agents were essentially telling J. Edgar Hoover that BMC was deviating from the acceptable norm.

To the agents, the school probably appeared to be the breeding ground for Communism. None of this was mentioned in the entirety of the museum exhibition. It had in fact been removed from all the literature about Black Mountain College. This could have been an act of negligence from the part of the curators, but in excluding any reference to the Red Scare, the ICA/Boston had essentially rewritten history.

To irritate the hole ridden history, I decided to modify the exhibition’s timeline. During my last shift at the museum, I wrote the words “commie art” in vinyl lettering. I used the same letters that were employed throughout the museum, and I stuck them in a place that wasn't in view of the cameras. At first, I thought my act would go unseen. This was the case until a fellow Visitor Assistant spotted the letters.

Multiple Visitor Assistants, Gallery Operator's, Visitor Experience Supervisors, Curators and Security Officer's flocked to the scene. For a reason I can't completely fathom, I was never a target of suspicion. I later discovered from my fellow museum employees, that my words were being considered an act of "vandalism," of mindless "graffiti."

Even though the words were probably immediately removed, they had served their desired purpose. The networks that structured the museum had been jarred, irritated. The museum space, had suddenly acquired a political edge. My primary achievement, was that my action wasn't considered art, for it didn't fit in to the unified corpus of the Museum’s border walls.

Political Art

Returning to the question planted previously: Do small political acts of resistance, such as stickers, unravel borderlines of our actuality? The answer is complex. Were my actions merely acts of vandalism? The act of irritation, when a structure of power is questioned, has definitive consequences. The walls of structures of systematic violence and metonymic censorship crumble when challenged from within.

Stickers, and many other art forms, can become agents of this irritation. When art is placed in unintended places, or in a manner that is unapproved by the existing authorities, it becomes political. Such an act politicizes a space that has become dormant. Placing art on border walls, unravels their very essence.

Reflected Manikins in "China: Through the Looking Glass" (2015), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.